| |

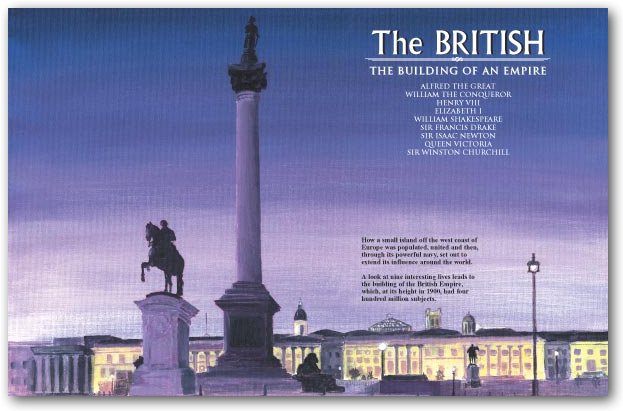

THE BRITISHTHE BUILDING OF AN EMPIREAlfred the Great | William the Conqueror | Henry VIII | Elizabeth I How a small island off the west coast of Europe was populated, united and then, through its powerful navy, set out to extend its influence around the world. A look at nine interesting lives leads to the building of the British Empire, which, at its height in 1900, had four hundred million subjects.

INTRODUCTIONAbout eight thousand years ago seawater flooded across the low lying land that connected Britain to Europe and Britain became an island. Ever since then the inhabitants of this island have never been sure whether they were part of Europe or not! The history of Britain is the history of invaders. Warriors from Europe who gained some control of the country then lost it to a new group of invaders. It is the story of war and intrigue, kings and exploration. It produced a unique blend of people of mixed heritage, speaking a flexible but wonderfully rich language. Initially their development lagged behind the rest of Europe but, through inventiveness, courage and energy, they would eventually rule the world’s sea routes and create an empire of almost 400 million subjects. BACKGROUNDEarly cavemen in Britain depended on animals for food and clothing and moved as the animals did. After hundreds of years, a new more sophisticated type of people from Mediterranean lands started arriving. Called “Beaker Folk” (after the cups they used for drinking) they brought with them a knowledge of metals which gave them superiority over the less well armed inhabitants. They were builders who seemed to have had a religion which we still don’t understand but we look at their mysterious temples of Stonehenge in awe. Small bands of settlers from the east continued to be drawn by stories of Irish gold and Cornish tin but there were no large invasions until about one thousand years before Christ, when migrating fair-headed Celts, also known as Gauls, crossed the English channel. They brought plows and oxen and traded metals with merchants from as far away as Greece. The Celts were proud of their appearance, combing their hair and adorning themselves with well-crafted jewelry. Divided into tribes, they occupied most of the southern part of Britain. One of the tribes the Brythons, gave the island its name. For hundreds of years the Celts raided each other’s forts, pushing west to Wales and Ireland, and north to Scotland. But everything was about to change — across the channel the Romans under Julius Caesar were conquering Gaul (France). THE ROMANSBy 55 BCE Caesar had defeated the Celts in Gaul, crossed the Rhine and pacified the German tribes. From the coast of France he looked across a narrow channel at a misty island. He knew many a defeated Gaul chief had evaded capture by retreating there and he was determined to pay Britain a visit. That August, with a small army he sailed across the channel. Behind him were his cavalry, in boats big enough to take horses. On land, the fierce Britons followed the Roman fleet along the coast until the invaders came ashore. At first the British warriors, shouting taunts and driving their war chariots to the waters edge, looked invincible but, as the Romans reached the beach, their superior discipline took over. Soon the Britons were suing for peace. Three days later, as the Romans prepared to receive their cavalry, a storm forced the horse boats to return to Gaul. Realizing the Romans were trapped, the Britons stopped the peace talks and attacked again. The Romans held them off long enough to repair the boats and then retreat back to France. Temporarily, Julius Caesar had to accept defeat but, by the next summer, his much larger fleet landed and marched up to the Thames River. This they crossed and, after a bitter engagement, the Britons surrendered. Caesar had avenged the previous forced withdrawal and given these wild tribes a taste of Roman power. With promises of tribute and a few hostages of noble birth he again withdrew to attend to Gaul and the ambitions that would make him the most powerful man on earth. For the next ninety years there was no formal Roman presence in Britain but trade with Roman Gaul flourished and Roman ideas and habits became widespread in Britain. In CE 43 the legions returned, this time under Aulus Plautius with 40,000 men accompanied by some military elephants. Once again, bitter fighting ensued but the Britons finally had to subject themselves to Roman rule. Peace came slowly however, and revolts against the Romans persisted, including one by Queen Boadicea of East Anglia who led enraged Britons from her chariot shouting “Death to the Romans” and insisting that they would never be slaves. She had initial success, including the defeat of the Roman Ninth Legion and the burning of the port of Londinium (London). But, once again, the Romans reorganized and drove the Queen’s forces back until Boadicea and her daughters drank poison in an open clearing to escape a more horrible death. The Romans had to deal with the religious Druids and destroyed their temples, then conquered Wales and turned their attention to the northern Picts in Scotland, which they called Caledonia. They built more than fifty well-organized towns and, as time passed, Britons were proud to be Roman citizens and behaved accordingly. The only hold-outs were the Picts and eventually Emperor Hadrian ordered that a wall be built from coast to coast to keep these Scottish warriors out of England. Now, the Scots joke that they use it to keep the English out of Scotland! The Roman Empire lasted for many centuries and, after its Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity in 337 CE, this new religion reached Britain, where it took hold among many Celts. But the Roman Empire was faltering. It was so weakened by barbarians, seeking the riches of Rome for themselves, that the Romans pulled out of Britain in 410 CE. THE ANGLES AND SAXONSAfter the Romans left, life in Britain became chaotic as work dried up and robber bands roved the countryside and towns, destroying and looting. These bands included the Picts from Scotland who penetrated as far as Kent in Southern England. To keep them in check, a Celt nobleman, Vortigern invited Saxons (from what is now Germany) to cross the sea and fight in his army. Soon, these heathen Saxons, as well as other European tribes like Angles and Jutes were strong enough in Britain to defy their hosts. There was resistance to their ascendancy, like that of Christian King Arthur who sat at a round table with his gallant knights. His victories over the heathen invaders were sung into legend about what would become a vanquished kingdom — Camelot. By 600 CE the pagan Anglo Saxons were masters of Britain and the country was called “England” (the land of the Angles). THE NORTHMENAs the year 800 approached, a new threat appeared along the coast of Britain. Even more terrible than the Barbarians were the Northmen, called Norsemen, Vikings or Danes. Traveling by longships and spreading across the countryside on stolen horses, they found easy pickings, raiding churches and abbeys and carrying off treasure and terrified captives. By 850 most of the easy treasure was exhausted and the Vikings changed tactics, moving in larger fleets (sometimes as many as 350 long-ships). They overran major ports and towns like London and Canterbury. The Anglo Saxons (many of whom were now Christians) resented these heathen Northern invaders and fought bravely for what they now considered their country. This effort produced a remarkable leader in King Alfred. | ||